Introduction

Founded in 1805 by settlers from Granville, Massachusetts, our village was built on ambition. Settled towards the end of Appalachia, the original dream was to transform Granville into a bustling industrial hub, rivaling nearby Newark, Ohio. Early residents invested in mills, manufacturing, and transportation, hoping industry would define the town’s future.

But when industry struggled to take root, Granville embraced its second vision—education. From early academies to the founding of Denison University in 1831, the village became a center for learning, culture, and community. Today, Granville is celebrated not for smoke-filled factories, but for its preserved architecture, rich history, and educational legacy.

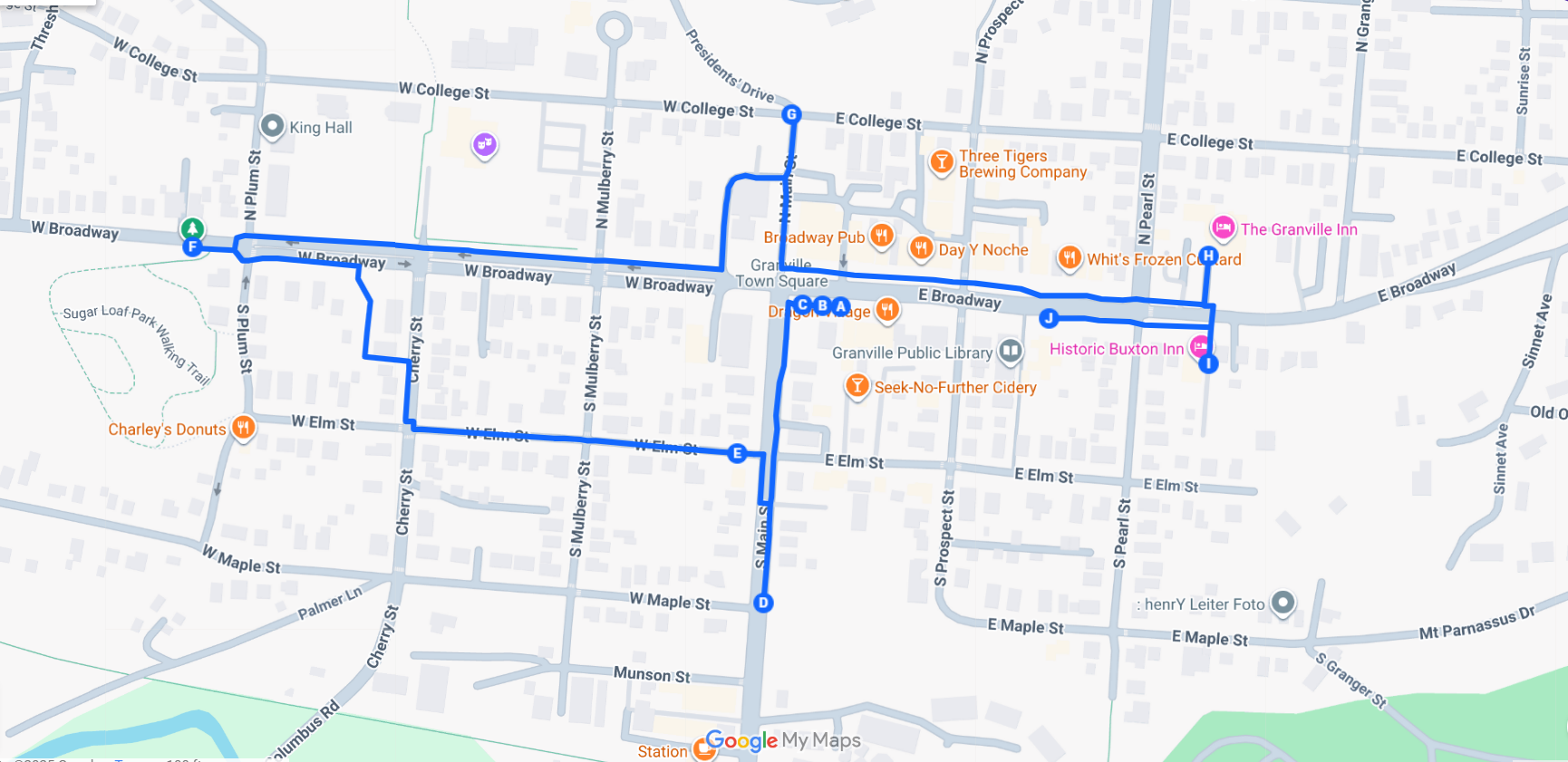

As you journey through this walking tour, each stop tells a part of that story, from the preserved landmarks of ambition, to the enduring institutions of knowledge

Follow the tour using the map in the Map section!

Granville Historical Society

The Granville Historical Society serves as the village’s cornerstone for historic preservation, operating out of one of Granville’s oldest and most significant buildings. Located on Broadway, the society is housed in the former Granville Bank. Constructed of a one story stone building, the Granville Bank stood as an early symbol of commercial life in Granville.

By the mid-20th century, the structure had fallen into disrepair, but a group of concerned citizens—determined to preserve Granville’s rich history—stepped in. In 1965, the Granville Historical Society was officially formed and took over the building, transforming it into a museum and archival space. The Granville Historical Society was founded by Charles Webster Bryant in 1885. The society found its home on Broadway in 1955.

Today, the interior of the society’s building hosts exhibits that showcase Granville’s evolution from a New England-founded frontier town into a thriving Ohio village. Artifacts on display range from 19th-century household goods and clothing to materials related to Denison University, local veterans, and Granville’s role in abolitionist movements. The society also preserves and interprets items from long-lost buildings, schools, businesses, and family farms, keeping their stories alive within the museum’s walls.

https://www.granvillehistory.org

In addition to the efforts Charles Webster Bryant made towards the Old Colony Burying Ground, he also established the Granville Historical Society.

In addition to the efforts Charles Webster Bryant made towards the Old Colony Burying Ground, he also established the Granville Historical Society.

St. Luke's Church

St. Luke’s Church in Granville, Ohio, stands as both a place of worship and a remarkable piece of architectural history compared to the other local churches. Its origins traces back to 1838 through the personal transformation of Lucius D. Mower, a local resident who became more religious after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. Facing the end of his life, Mower shared a powerful testimony that deeply moved his brother, Sherlock Mower. After Lucius passed, Sherlock chose to honor his brother’s final wishes by funding the construction of a church in his memory.

The result was the creation of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, designed by architect Benjamin Morgan. Morgan, who also drafted the original plans for the Ohio State Capitol in Columbus, brought a grand and timeless style to the church. Completed in the mid-19th century, the building quickly gained attention for its beauty and detail. The church is widely considered one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the United States. In 1976, it was officially added to the National Register of Historic Places.

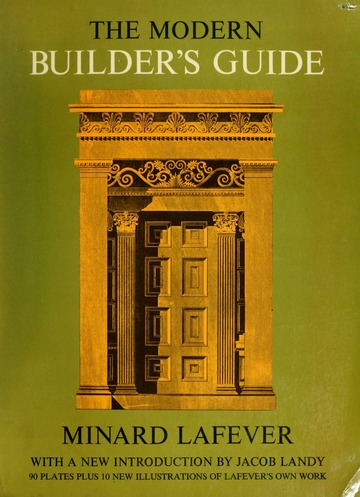

St. Luke’s features several original elements that have been carefully preserved. These include the box pews, a decorative plaster ceiling medallion, and an elegant chandelier that still hangs in the main sanctuary. The interior design was created by Minard Lafever, a well-known architect of the time who worked in cities like New York and New Orleans. Lafever also wrote several influential books on architecture, and his signature style added another layer of importance to the church’s design.

More than just a historic building, St. Luke’s represents a meaningful story of personal faith and family legacy. What began as one man’s reflection in the face of illness became a gift that continues to serve the Granville community nearly two centuries later. The church remains active today, not only as a place for worship, but also as a lasting reminder of the town’s heritage and dedication to preserving its past.

https://www.stlukesgranville.org

In the month of October, the Granville Historical Society puts on the annual Ghost Walk. Pictured above are actors portraying the Mower family including: Lucius Mower, Sherlock Mower, Isabella Mower Richards.

In the month of October, the Granville Historical Society puts on the annual Ghost Walk. Pictured above are actors portraying the Mower family including: Lucius Mower, Sherlock Mower, Isabella Mower Richards.

Pictured above is 1 of the 5 architectural books that LaFever wrote throughout his lifetime. These books heavily influenced the idea of Greek Revival architecture.

Pictured above is 1 of the 5 architectural books that LaFever wrote throughout his lifetime. These books heavily influenced the idea of Greek Revival architecture.

Opera House Park

The Granville Opera House stood as a proud symbol of the village’s rich cultural history and commitment to the arts. Located in the heart of Granville’s downtown, the Opera House was originally built in 1849 as the First Baptist Church and was moved to the southeast of South Main Street. In 1882 it was raised one story and quickly became a central gathering place for entertainment, social events, and public meetings. Designed to accommodate a variety of performances—from traveling theatrical productions to local concerts and lectures—the building served as a vibrant hub where residents could experience the arts and engage with one another.

The Opera House’s architecture reflected the style and craftsmanship of the late 19th century, featuring large windows that invited natural light into the auditorium. Inside, the theater’s stage and seating area were designed to provide good sightlines and acoustics, ensuring an enjoyable experience for audiences of all sizes. Over the years, the venue hosted plays, musical performances, political speeches, and community celebrations, helping to enrich the cultural life of Granville and the surrounding region.

Unfortunately the building itself encountered a fire caused by an egg incubator in one of the offices, and burned down in 1982. The bell from the building steeple is all that remains-marking the entrance to Opera House Park.

Before the Opera House burned down, here is what the former building looked like.

Before the Opera House burned down, here is what the former building looked like.

Old Colony Burying Ground

The Old Colony Burying Ground, established in 1805 and first used for burials in 1806, is the original cemetery of Granville, Ohio. Laid out on the earliest town plat by the settlement’s founders, it features its oldest remaining gravestone from 1807 and continues to serve as the final resting place for the village’s earliest residents—including Revolutionary War veterans, settlers, civic leaders—reflecting the diversity of those who built the community.

Spanning over 2,000 interments—though only about 950 are marked—the cemetery holds the graves of local pioneers like Timothy Rose, Granville's first church deacon, and Jesse Munson an early founder of Granville, both of whom died in 1813. The headstones offer a visual record of local craftsmanship, evolving from sandstone markers carved by artisans Thomas and Rollin Hughes to later marble monuments that arrived via the Ohio & Erie Canal.

Noted local historian Charles Webster Bryant meticulously recorded nearly 1,000 epitaphs in 1886—a vital resource when many stones weathered beyond legibility. Webster died of a fever within a few months after his work on the Old Colony Burying Ground. In 1912, the Granville Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution spearheaded restoration efforts and installed the wrought-iron entrance gates that still bear the “Old Colony Burying Ground” inscription today. The Old Colony Burying Ground is still going through ongoing restoration funded by the insurance settlement of the Opera House fire that occurred.

Pictured above is the grave of Timothy Rose, Granville's first church deacon in the congregational church.

Pictured above is the grave of Timothy Rose, Granville's first church deacon in the congregational church.

Pictured above is Charles Webster Bryant, whose efforts greatly helped record the gravestones of those buried at the Old Colony Burying Ground.

Pictured above is Charles Webster Bryant, whose efforts greatly helped record the gravestones of those buried at the Old Colony Burying Ground.

The Old Academy Building

The Granville Academy Building played a key role in the early history of education in Granville, Ohio. It began in 1827, when Mary Ann Howe opened a school for young women on the site where the Granville Public Library now stands. At a time when educational opportunities for women were limited, this school was a progressive effort to offer academic instruction beyond the basics. The building itself was modest but functional, with its upper two stories divided into classrooms that supported a growing student population.

Between 1835 and 1837, enrollment grew rapidly—from 65 students to 175 young women. To accommodate this growth, the school expanded in 1838 onto land that is now the site of the Granville Inn, with women staying at the original location and men moving to this Main and Elm Street location. The curriculum at the time reflected an academy-style education, which was rigorous for its day. Students studied subjects such as algebra, geometry, botany, natural philosophy (a precursor to science), and United States history. The school’s academic environment and structure made it one of the more notable educational institutions for women in the region. The building was then purchased by the Welsh Congregational Church in 1863.

However, despite its early success, the academy eventually disbanded. One of the main reasons was that the school’s curriculum more closely resembled a secondary education rather than a college-level program. As public schools became more common in Ohio, the need for private academies like this one began to fade. The building itself also became outdated over time, and its architecture posed challenges for repairs and updates.

The Old Academy Building was also a proponent in the anti-slavery movement. An abolitionist by the name of Theodore Weld had eggs pelted at him while standing inside the Old Academy Building. At the time there was a trial occurring over a runaway slave.

Though the Granville Academy Building no longer exists as a school, its impact is still remembered. It represents one of the earliest serious efforts to provide structured education for women in the community. The site helped lay the groundwork for the value Granville continues to place on learning and access to education. Today, its legacy lives on not just in the physical location, but in the town’s continued focus on schools, libraries, and institutions of higher learning.

Because of the rapidly increased enrollment, the school expanded on to the site of the present day Granville Inn. The image above depicts the growth that the Granville female education experienced.

Because of the rapidly increased enrollment, the school expanded on to the site of the present day Granville Inn. The image above depicts the growth that the Granville female education experienced.

Sugar Loaf Hill is a sandstone rise just outside the heart of Granville, Ohio. Initially during the settlement of Granville, there was a significant snake problem the colonizers encountered. Many of the settlers would drive the snakes up to Sugar Loaf Hill and kill them. While it is a peaceful non-snake ridden spot today, its appearance and purpose have changed greatly over time. In the 1800s, the six-acre hill was heavily stripped of its trees by local residents who used the land for livestock pasture, firewood, and even for digging up foundation stones. At one point, the hill’s west side was intentionally cleared by a frustrated landowner who disliked the noise made by squirrel hunters. By the end of the 19th century, the once-wooded hill had become barren and neglected—but that would soon change through the efforts of Granville’s citizens.

On April 1, 1896, a committee gathered to discuss turning Sugar Loaf Hill into a public park. Although the village government lacked the funds to make this happen, local residents raised $300 on their own to support the project. With the money, they built a driveway, raised a flagpole, and planted more than 300 trees to restore the hill’s natural beauty. The effort brought together many groups, including Methodist donors who planted mountain ash trees, alumnae from Shepardson College who donated white birch, and members of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity who contributed a mulberry tree. This project was one of the key events that led to the formation of the Granville Civic and Village Improvement Society.

The reforestation and park creation turned Sugar Loaf Hill into more than just a scenic spot—it became a symbol of civic pride and cooperation. During the Centennial Year in 1905, a seven-ton glacial boulder was hauled to the top of the hill and placed on a granite base both brought from Granville, Massachusetts, the original home of many of the town’s settlers. This event tied the natural history of the land with the cultural roots of the community, showing how the people of Granville valued both their environment and their shared past.

Today, Sugar Loaf Hill stands as a quiet but meaningful landmark. Its transformation from a stripped and overused pasture into a cared-for community park reflects the town’s commitment to conservation and civic improvement. Whether it’s used for walking, reflection, or learning local history, Sugar Loaf remains a place where Granville's natural beauty and community values come together.

As pictured above, this image depicts the glacial boulder taken up to the top of Sugar Loaf Park during the Centennial Year in 1905. As described, much of the trees and nature that make Sugar Loaf Park what it is today, were stripped out. This represents the immense change that Sugar Loaf Park experienced.

As pictured above, this image depicts the glacial boulder taken up to the top of Sugar Loaf Park during the Centennial Year in 1905. As described, much of the trees and nature that make Sugar Loaf Park what it is today, were stripped out. This represents the immense change that Sugar Loaf Park experienced.

The image above represents the great change that Sugar Loaf Park has gone through, as depicted by the increased amount of trees.

The image above represents the great change that Sugar Loaf Park has gone through, as depicted by the increased amount of trees.

Denison University

Denison University was founded in 1831 and is one of the oldest colleges in the old Northwest Territory. It first opened as the Granville Literary and Theological Institution, created by Baptist settlers who wanted to offer higher education and religious training in the area.

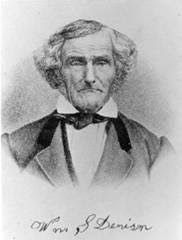

In 1856, Judge William Denison donated a large sum of money to the school, and it was renamed in his honor. Over the years, Denison grew from a small religious school into a well-known liberal arts college. Its campus sits on a hill overlooking Granville and includes historic buildings like Swasey Chapel and Doane Library. The university is known for strong programs in the arts, sciences, and humanities, as well as small class sizes and close relationships between students and professors.

Today, Denison continues to bring students from across the country while staying connected to Granville’s history.

Denision Magazine: https://denison.edu/magazine/2007-issue-3/139939

Denison University Homepage: https://denison.edu

Pictured above is William S. Denison, who is the famous name of the college settled in Granville Ohio but a person who also took down a bear with just a knife. Check out the link to the Denison Magazine Issue.

Pictured above is William S. Denison, who is the famous name of the college settled in Granville Ohio but a person who also took down a bear with just a knife. Check out the link to the Denison Magazine Issue.

Granville Inn

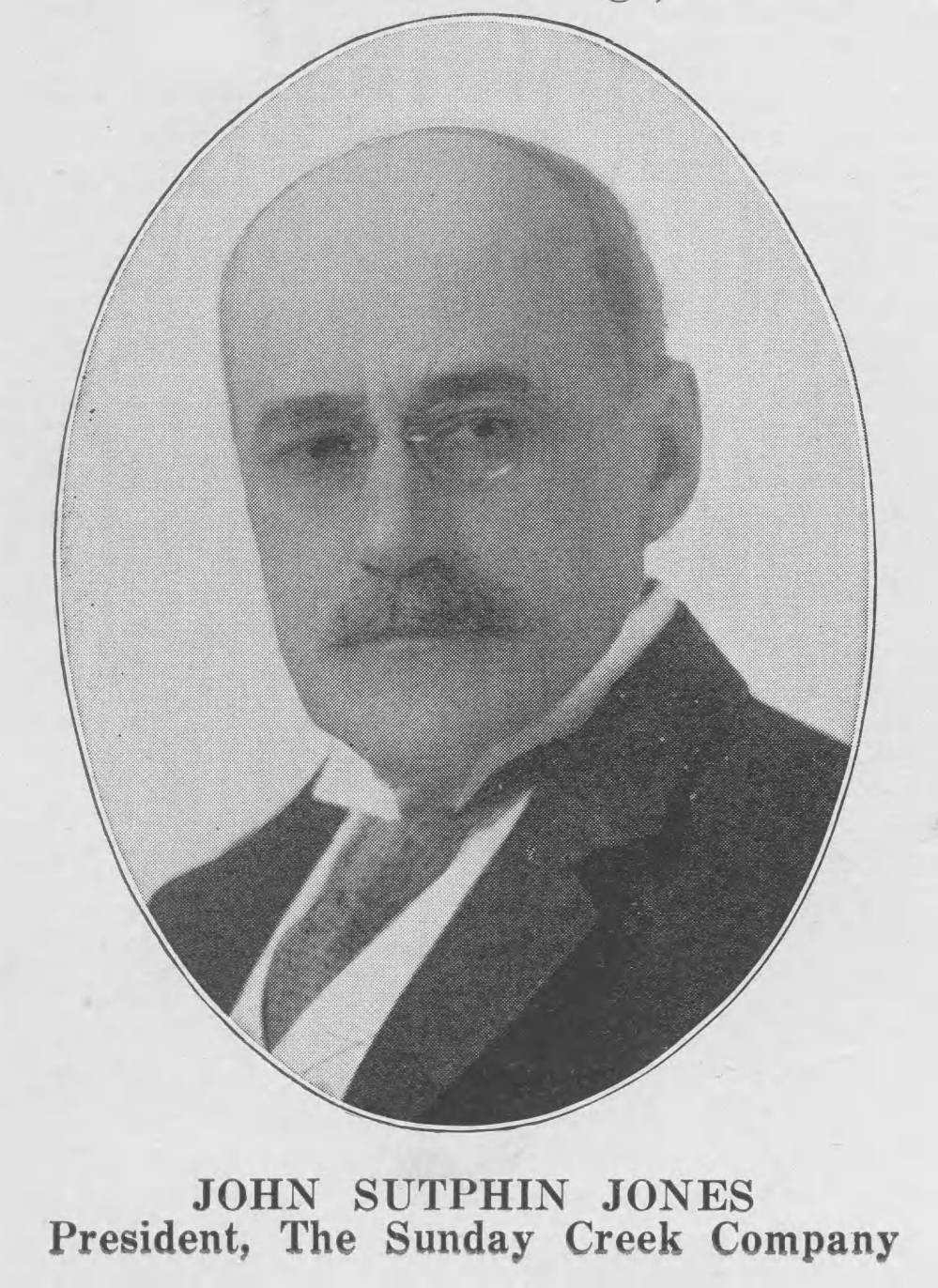

The Granville Inn stands as a testament to the enduring commitment to community and hospitality in Granville, Ohio. Constructed on the site of the Granville Female College in June 1924, the inn was the vision of John Sutphin Jones, a prominent local entrepreneur who amassed considerable wealth through his ventures in coal and transportation. While working many jobs, such as the T & OC (Toledo and Ohio Central) railroad he developed a love for Granville.

Jones wanted the Inn not to serve as just another “good enough” place as Jones envisioned the inn as a luxurious retreat that would not only serve travelers but also act as a social hub for Granville's residents. But Jones kept the needs of the town in mind, as the Granville Inn did not start being built until much needed infrastructure improvements were made throughout Granville. Making a deal with the village elders if they had provided renovations in electricity, sewers, and the development for a water plant, only then would he build a good hotel for Granville.

Working with architect Frank L. Packard, who previously designed renovations for the Bryn Du estate, Jones' vision would become a reality. Its architectural design reflects the Tudor style, featuring oak-paneled rooms, intricate stonework, and manicured gardens, embodying an ambiance of refined elegance. The Inn included natively sourced products such as quarried sandstone from the hillside of the Bryn Du estate, which also housed Jones in the summer months. Within the Inn, no 2 rooms of the original 24 bedrooms were alike, demonstrating the diversity of the hotel.

Buxton Inn

The Buxton Inn is one of the oldest buildings in Granville, Ohio, and has been in operation since 1812. It was originally built as The Tavern by Orrin Granger, one of the town’s early settlers. Over the years, it has served many purposes, including as a stagecoach stop, post office, and gathering place for the community. The building’s design reflects early 19th-century architecture, and it still has many of its original features, including fireplaces, woodwork, and stone walls.

The inn has always been a central part of Granville’s identity. Throughout its long history, it has welcomed guests from all over the country and even some famous visitors, such as President William H. Harrison. Locals and tourists alike have come to the Buxton Inn to dine, stay overnight, or attend events in its historic setting. Its close connection to the town and to Denison University has made it a regular place for students, professors, and families to visit.

Even though the Buxton Inn has been around for over 200 years, it has been carefully maintained and updated to meet modern standards. While improvements have been made, the owners have worked to keep the original character of the building intact. Visitors can still see the old stone floors, wood beams, and period décor, which help the inn feel like a step back in time.

Prior to the Buxton Inn, the site was known as The Tavern. As The Tavern represented a stagecoach route that cam through Granville, many of the drivers, brakemen, and butlers had beds in this basement bar.

Prior to the Buxton Inn, the site was known as The Tavern. As The Tavern represented a stagecoach route that cam through Granville, many of the drivers, brakemen, and butlers had beds in this basement bar.

Robbins Hunter Musuem

Constructed in 1842, the Robbins Hunter Museum stands as a treasured landmark in Granville, Ohio, offering visitors a unique glimpse into the village’s history and early life. The museum preserves the heritage of Granville’s founding families and the evolution of the community. The museum’s exhibits and collections focus on local history, architecture, and daily life, helping to bring the stories of the past to life for modern audiences.

The original structure, known as the Avery Downer house, was prominent with the early settlers in Granville. The building showcases period furnishings, artifacts, and documents that reflect Granville’s growth from a frontier settlement to an established village. The museum also highlights the craftsmanship and architectural styles of the time displaying Greek Revival Architecture.

On the west side of the building, the clock tower marks the hours with bells and the appearance of a statue of Victoria C. Woodhull, the first woman to run for President of the United States in 1872. She was also a staunch advocate for women’s rights.

Beyond its role as a historical exhibit, the Robbins Hunter Museum actively engages the community through educational programs, special events, and tours. These activities aim to deepen understanding and appreciation of Granville’s cultural roots, making history accessible to visitors of all ages. The museum serves as a gathering place where people can connect with the village’s past and gain insight into the experiences that shaped the present.

Thank You!

I would like to thank the Granville Historical Society specifically: Nanette Maciejunes, Jack Wheeler, Lyn Boone, Tom Martin, and Theresa Overholser for assisting with my Eagle Project. I would also like to thank Denison University specifically Lori Robbins, along with Scouting America Troop 4065 for their partnership and collaboration with building The Granville Ohio Historical Walking Tour as my Eagle Scout Service Project. My goal for this project is to inspire our community by sharing stories of resilience and innovation, while at the same time providing perspective, reminding us that challenges are often temporary and manageable. I really hope you enjoyed the tour as much as we did creating it! Feel free to check out the other locations bellow that are not part of the walking tour.

- William Bukala (Granville Troop 4065)

- Completed October 25, 2025

The Bancroft House

Built in 1834, the Bancroft House at 555 North Pearl Street may seem like a quiet, stone-fronted home, but its history speaks volumes. Named after its builder and original owner, Ashley Azariah Bancroft, the house has long been tied to the abolitionist movement in Granville, Ohio. Bancroft, a descendant of Samuel Bancroft—the founder of Granville, Massachusetts—was described as an “ardent abolitionist” by the Granville Historical Society. In 1836, just two years after the house was completed, Ashley Bancroft hosted the first meeting of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in a barn on the property, sparking what became known as the “Great Riot of 1836.” The event caused division in the town, with some residents threatening society members and condemning the meeting’s purpose. Still, the Bancroft property quietly became a safe haven, and like other homes on North Pearl Street, it played a key role in the Underground Railroad.

Ashley Bancroft’s son, Hubert Howe Bancroft, was sent by his family to use a hay wagon to smuggle escaped slaves hidden beneath hay bales when he was a boy, helping them travel north toward Mt. Vernon. H. H. Bancroft would grow up to become one of the most well-known historians of the 19th century, with the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley named in his honor. The Bancroft House and others nearby, like the Langdon House at 235 North Pearl Street, were considered ideal for Underground Railroad activity due to their location away from Granville’s center. The quiet street provided cover for those risking their lives to support the anti-slavery cause. Bancroft’s courage, along with that of his family and allies, helped push the movement forward in Central Ohio at a time when it was not only unpopular but dangerous.

In 1917, the historic Bancroft House entered a new chapter when Denison University purchased it. For 80 years it served as a faculty residence, but in 1997, the building was repurposed as a student residence hall—specifically, one reserved for female students. According to Denison’s housing office, Bancroft House is the only off-campus satellite house set aside exclusively for women, offering a unique living experience grounded in history. Students living there today walk the same halls where major decisions and daring actions once took place, continuing a tradition of community and resilience in a more peaceful era.

Though rumors persist about a hidden tunnel beneath the house, none have been confirmed. Still, students like Kirstie Rodden ’16 recognize the historical weight of their residence. What began as a private home built by a forward-thinking abolitionist has since become a symbol of Granville’s role in social progress. The Bancroft House remains a quiet but powerful reminder that history lives not only in books, but also in the spaces we pass by every day.

In the month of October, the Granville Historical Society puts on the annual Ghost Walk. Pictured above are the Munson family including: Lucius Mower, Sherlock Mower, Isabella Mower Richards.

In the month of October, the Granville Historical Society puts on the annual Ghost Walk. Pictured above are the Munson family including: Lucius Mower, Sherlock Mower, Isabella Mower Richards.

Bryn Du Mansion

Set on the eastern edge of Granville, Ohio, the Bryn Du Mansion has stood for over 160 years as a symbol of changing times, ambitious vision, and civic pride. Originally built in the 1860s by businessman Henry D. Wright, the mansion was first designed as an Italianate Villa made from sandstone quarried directly from the estate’s grounds. Within a year of completion, the property was sold to Jonas McCune and came to be known locally as McCune’s Villa. Though it changed hands several times after that, its transformation into a landmark estate began in 1905, when John Sutphin Jones—an industrialist who had made his fortune in coal and railroads—purchased the property.

Jones brought in prominent Columbus architect Frank Packard to oversee a full redesign. Over five years, the villa was reshaped into a Georgian-Federal style mansion with outbuildings, transforming it into the estate known today. The project was only the beginning of Jones’s influence on Granville’s landscape. In 1922, he and Packard collaborated again to design and construct the Granville Inn. Just a few years later, Jones commissioned famed golf course designer Donald Ross to build the Granville Golf Course—one of the few Ross courses that he personally oversaw. During Jones’s time at Bryn Du, the mansion became a social center, hosting guests such as Presidents Calvin Coolidge, William Howard Taft, and Warren G. Harding, as well as cultural figures like Lillian Gish, Paderewski, and Rachmaninoff.

When Jones passed away in 1927, the property was inherited by his daughter, Sallie Jones Sexton. Known throughout the region for her vivid personality and strong opinions, Sallie managed the estate and the Granville Inn while also operating a nationally recognized horse breeding business. Though she became a local legend, her management style eventually led to the financial decline of the estate, ending in bankruptcy. Over the next few decades, the property passed through multiple owners. The Wright family purchased it at auction in 1976 and briefly operated a restaurant on the premises in the mid-1980s. Quest International later used the mansion as its corporate headquarters before moving out in the 1990s, leaving the house empty once again.

In 2002, Granville residents voted in favor of acquiring the mansion, and the Village of Granville purchased the estate from the Longaberger Company. Since then, the Bryn Du Mansion has been managed by the Bryn Du Commission, which was formed to maintain the historic property and ensure its use for cultural, educational, and recreational events. Today, the estate remains a vital part of the community—hosting public gatherings, performances, and exhibitions—while preserving the architectural and historical character that has defined it for generations.

This picture shows Presidents William Howard Taft and Calvin Coolidge, just two of the presidents that have paid a visit to the Bryn Du Mansion.

This picture shows Presidents William Howard Taft and Calvin Coolidge, just two of the presidents that have paid a visit to the Bryn Du Mansion.

Pictured above is Sallie Jones Sexton, the daughter of John Sutphin Jones. Inheriting the Bryn Du from her father, she managed to balance this along with managing a horse breeding business.

Pictured above is Sallie Jones Sexton, the daughter of John Sutphin Jones. Inheriting the Bryn Du from her father, she managed to balance this along with managing a horse breeding business.

Walter J. Hodges Stadium

Walter J. Hodges Stadium stands as the centerpiece of Granville High School athletics, located just off New Burg Street on the school campus. Opened in 2020, the stadium is home to the Blue Aces’ football, soccer, field hockey, lacrosse, and track & field teams. With its modern artificial turf, updated eight-lane track, and seating for nearly 2,400 spectators, the stadium serves not only as a competitive arena but also as a space for school and community celebrations. It is a place where athletes grow, students gather, and traditions are made—carrying the spirit of Granville forward every season.

The stadium is named in honor of Walter J. Hodges, a devoted educator and administrator who left a lasting mark on Granville Schools. Often referred to as Jesse Hodges in school yearbooks, he had been a hard-working kid; working as a caddy at the age of 9 along with being a lifeguard at the Spring Valley Pool. He won a state football championship in 1959: demonstrating athletic excellence at a young age. He also had a sister named Lou Hodges Reese, whose name appears on the fields scoreboard.

Beyond athletics, Hodges Stadium plays a wider role in the life of the Granville community. The stadium hosts annual events like high school graduation, youth sports camps, and recreational activities organized by the Granville Recreation District. It is a venue that welcomes not just high school athletes, but families, alumni, and local residents who come to cheer, compete, and connect. From packed Friday night football games to quiet early morning track practices, the field represents a shared investment in the well-being and success of Granville’s youth.

Pictured above is the Granville High School Marching Band on a Friday home football game, one of the more popular events in Granville.

Pictured above is the Granville High School Marching Band on a Friday home football game, one of the more popular events in Granville.

Works Cited

“Bancroft House Rooted in Anti-Slavery and the Underground Railroad.” The Denisonian, 2015, denisonian.com/2015/10/features/bancroft-house-rooted-in-anti-slavery-and-the-underground-railroad.

Evans, Laura. Granville’s Tycoon: John Sutphin Jones and the Gilded Age. Granville Historical Society, 2020.

“Our History.” Bryn Du Mansion, https://www.bryndu.com/our-history. Accessed 11 Oct. 2025.

“The History of the Granville Inn.” Granville Inn, granvilleinn.com/history-of-inn/. Accessed 13 Apr. 2025.

Utter, William Thomas. Granville: The Story of an Ohio Village. Granville Historical Society : Denison University, 1987.

Wilhelm, Clarke L., et al., editors. Granville, Ohio: A Study in Continuity and Change. Vol. 1–2, Granville Historical Society : Denison University Press, 2004.